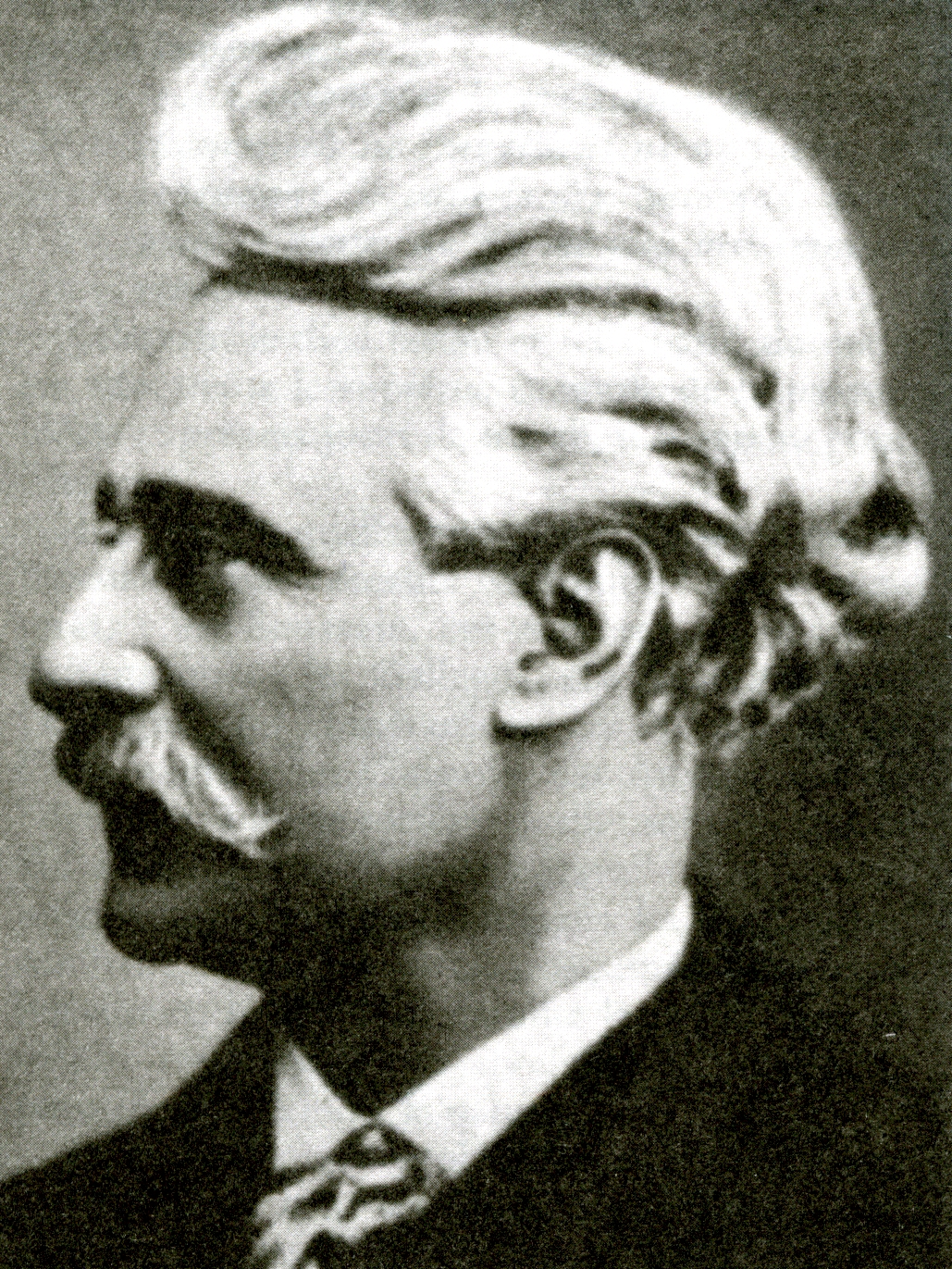

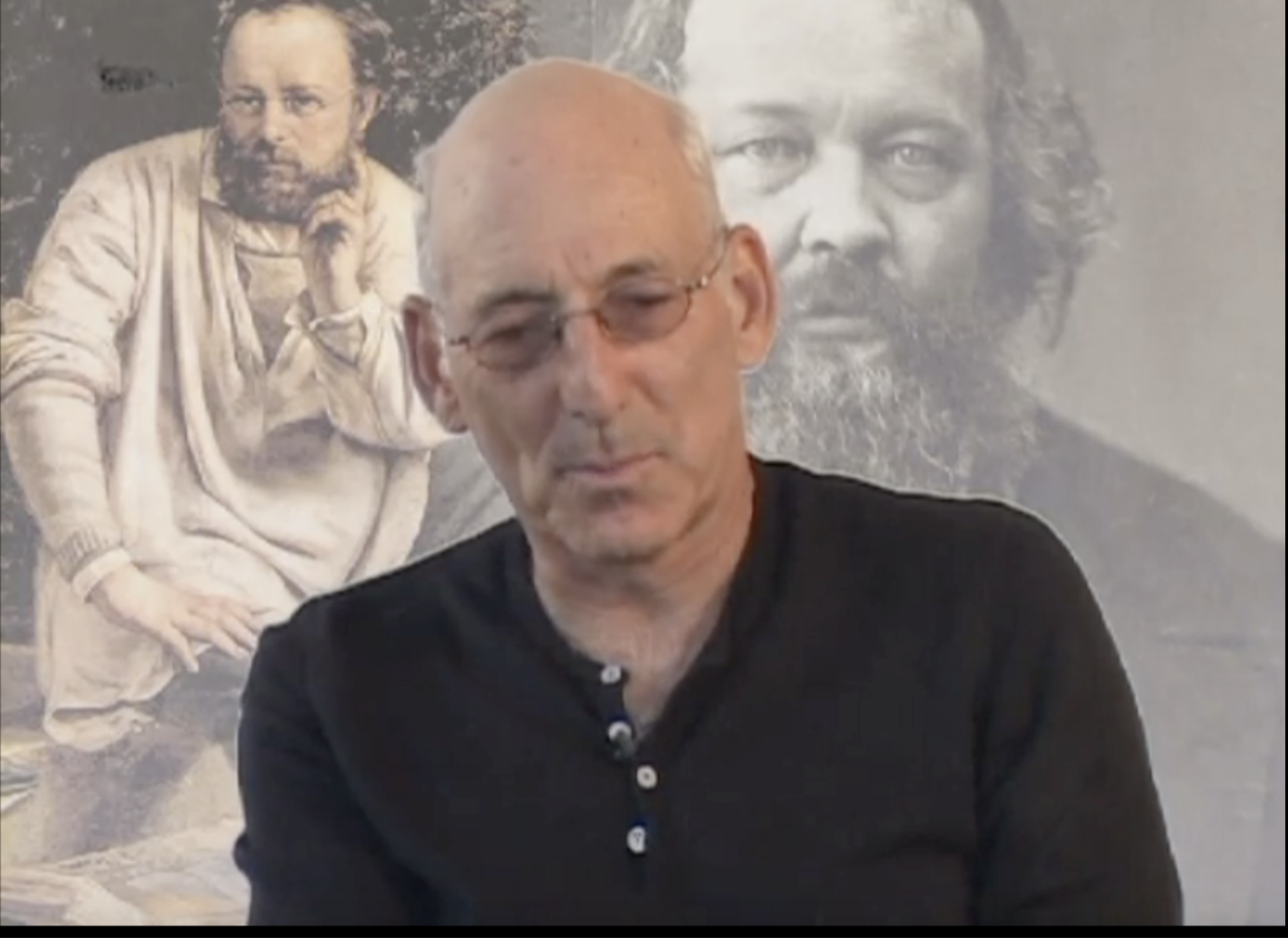

Russell Jacoby (b. 1945) – Selected Works

Academic Marxism is hardly the whole of the political Left. Recent symposiums on the Left have stressed that the goals of the past decades have not been met: racism, poverty, discrimination, remain current realities; the 80s will see groups trying to survive in the teeth of government retrenchment and recession. This is undeniable. The struggle to survive cannot be criticized; yet it has little to do with the fate of a political Left. Nor is this an insult. The Left has often confused oppression with revolution; the most oppressed were the most blessed. Yet it belongs to basic Marxism that there is no automatic link between suffering and revolutionary activity. Marx never argued that the working class suffered more than the peasantry. The specific conditions of the working class prompted the hope of revolution. That various socioeconomic groups and minorities are in for a bad deal in the coming years, cannot be doubted. It can be doubted that they will cross the line separating the struggle to eat from the struggle for emancipation. Those who are sound in body and mind will not fight the revolution; those who are mutilated beyond repair cannot: this is the curse which has bewitched the revolutionary project.

The next years will be the era of partial struggles. Groups will enter the political arena to do battle for separate rights and interests: rent control, health care, environment, and so on. It would be arrogant to write any of this off. A wildcat strike to preserve a coffee break which is being eroded away is surely justified. Yet the struggles are fragmentary, local and transitory. The whole is elusive. If the strength of contemporary radicalism is its localism, this is also its weakness. As always the danger is in self-righteousness and self-mystification: the confusion of better garbage collection with revolution. Apart from any ends which are achieved, partial struggles keep alive an arena for political activity and commitment; for many individuals this will be critical — and more: a renaissance of political activity is unthinkable without the participation of individuals. When the conditions change, those who have remained in the daily fray may be able to show the way. To be sure, in the rat race of daily politics they may also forget the way.

– Russell Jacoby, “Crisis of the Left?” (1980)

Books:

Russell Jacoby – The end of utopia_ politics and culture in an age of apathy-Basic Books (2000)

Russell Jacoby – The Last Intellectuals_ American Culture in the Age of Academe, 2nd edition (2000)

Russell Jacoby – The Repression of Psychoanalysis

russell jacoby – dialectic of defeat: contours of western marxism

russell jacoby – picture imperfect: utopian thought for an anti-utopian age

russell jacoby- social amnesia: a critique of contemporary psychology from adler to laing

Essays and Reviews:

Real Men Find Real Utopias _ Dissent Magazine

Argument_ Michael Burawoy and Russell Jacoby _ Dissent Magazine

jacoby laing cooper and the tension in theory and therapy

jacoby marcuse and the new academics

jacoby narcissism and the crisis of capitalism

jacoby politics of crisis theory II

jacoby postscript to authoritarian state

jacoby review of the political philosophy of the frankfurt school

jacoby the politics of objectivity

jacoby the politics of subjectivity

jacoby towards a critique of automatic marxism

jacoby what is conformist marxism