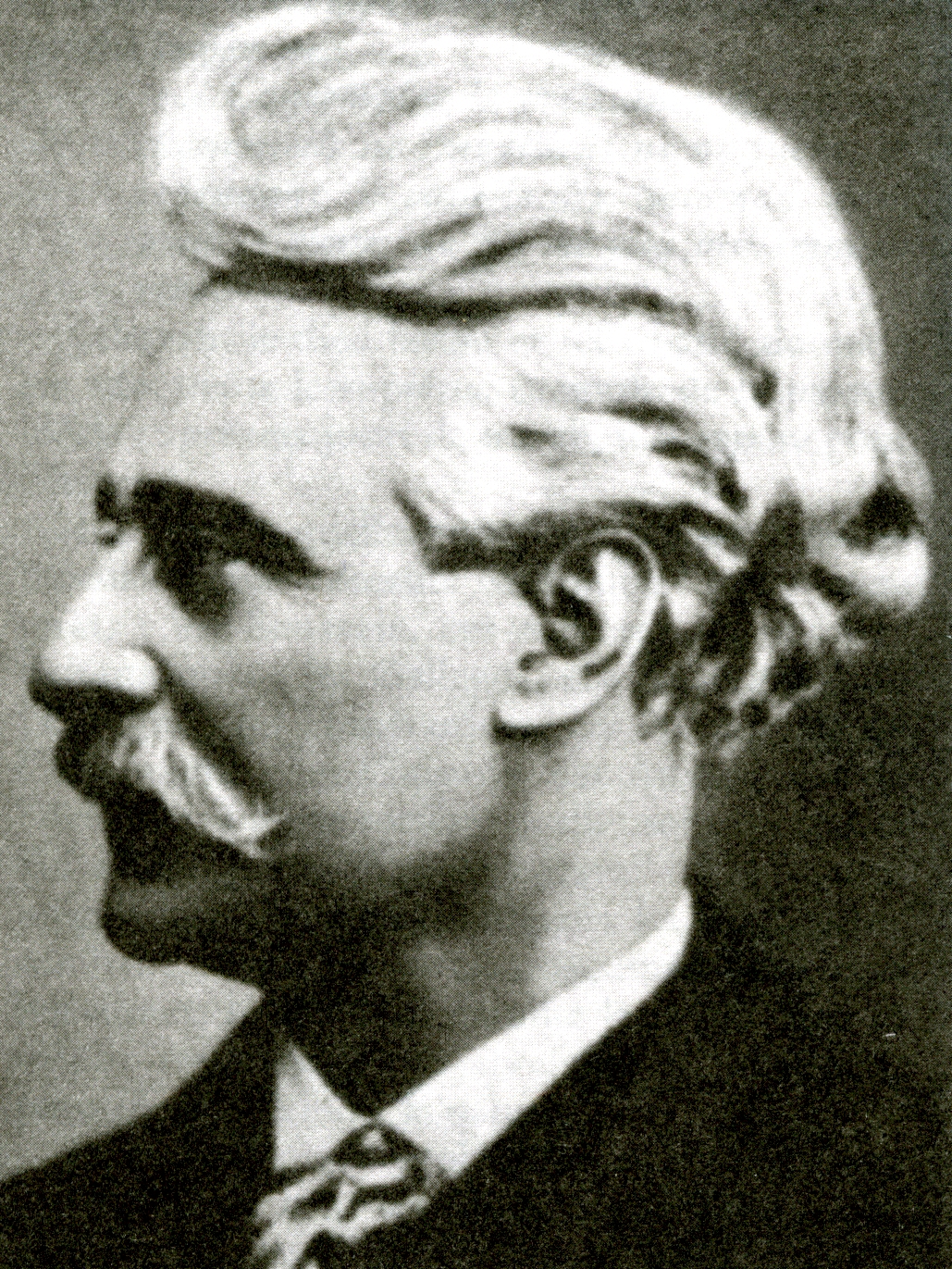

For Socialism (Landauer, 1911)

See also: Landauer: Revolution and Other Writings / All Power to the Councils!

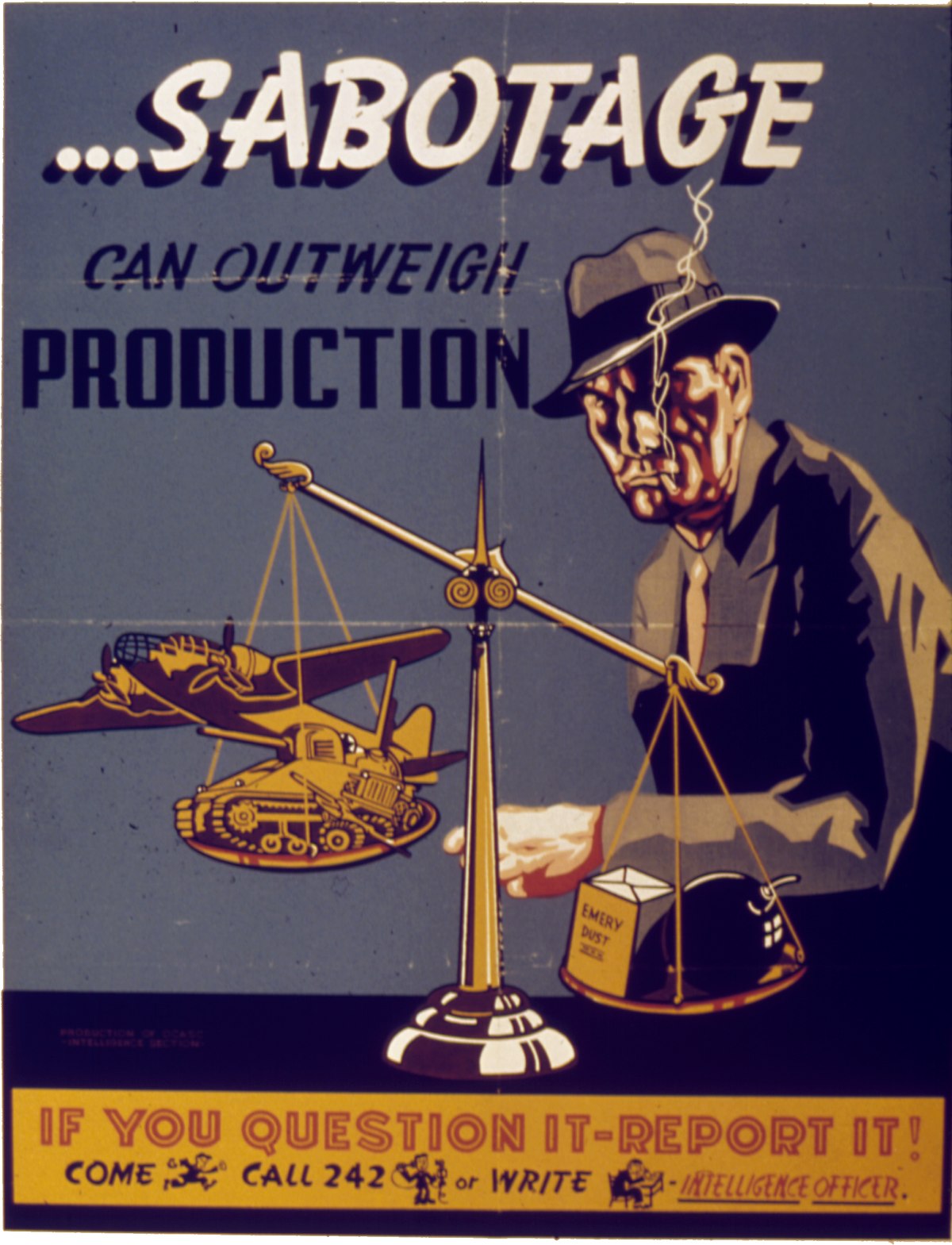

For socialism — let it be said immediately and the Marxists ought to hear it, as long as the wisps of fog of their own obtuse theory of progress are still in the air — does not depend for its possibility on any form of technology and satisfaction of needs. Socialism is possible at all times, if enough people want it. But it will always look different, start and progress differently, depending on the level of available technology, i.e., also of the number of people who begin it and the means they contribute or have inherited from the past — nothing begins from nothing. Therefore, as was said above: no depiction of an ideal, no description of a Utopia is given here. First, we must examine our conditions and spiritual temperaments more clearly. Only then can we say to what kind of socialism we are called, to what type of men we are speaking. Socialism, you Marxists, is possible at all times and with any kind of technology. It is possible for the right people at all times, even with very primitive technology, while at all times, even with splendidly developed machine technology it is impossible for the wrong group. We know of no development that must bring it. We know of no such necessity as a natural law. Now therefore we will show that these our times and our capitalism that has blossomed as far as Marxism are by no means as you say they are. Capitalism will not necessarily change into socialism. It need not perish. Socialism will not necessarily come, nor must the capital-state-proletariat-socialism of Marxism come and that is not too bad. In fact no socialism at all must come — that will now be shown.

Yet socialism can come and should come — if we want it, if we create it — that too will be shown.

– Gustav Landauer, 1911