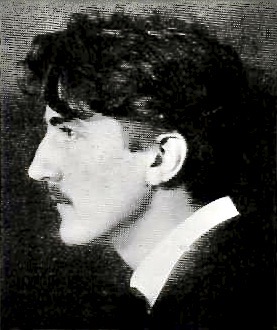

Karl Korsch (1886-1961)

“Marxism as an historical phenomenon is a thing of the past. It grew out of the revolutionary class struggles of the first half of the nineteenth century, only to be maintained and re-shaped in the second half of the nineteenth century as the revolutionary ideology of a working class which had not yet regained its revolutionary force. Yet in a more fundamental historical sense, the theory of proletarian revolution, which will develop anew in the next period of history, will be an historical continuation of Marxism. In their revolutionary theory, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels gave the first great summarization of proletarian ideas, in the first revolutionary period of the proletarian class struggle. This theory remains for all time the classical expression of the new revolutionary consciousness of the proletarian class fighting for its own liberation.” – The Crisis of Marxism, 1931

Books (pdfs):

Marxism and Philosophy (1923) – by Karl Korsch

Karl Marx (1938) – by Karl Korsch

Karl Korsch: Revolutionary Theory – edited by Douglas Kellner (1977)

Karl Korsch: A Study in Western Marxism – by Patrick Goode (1979)